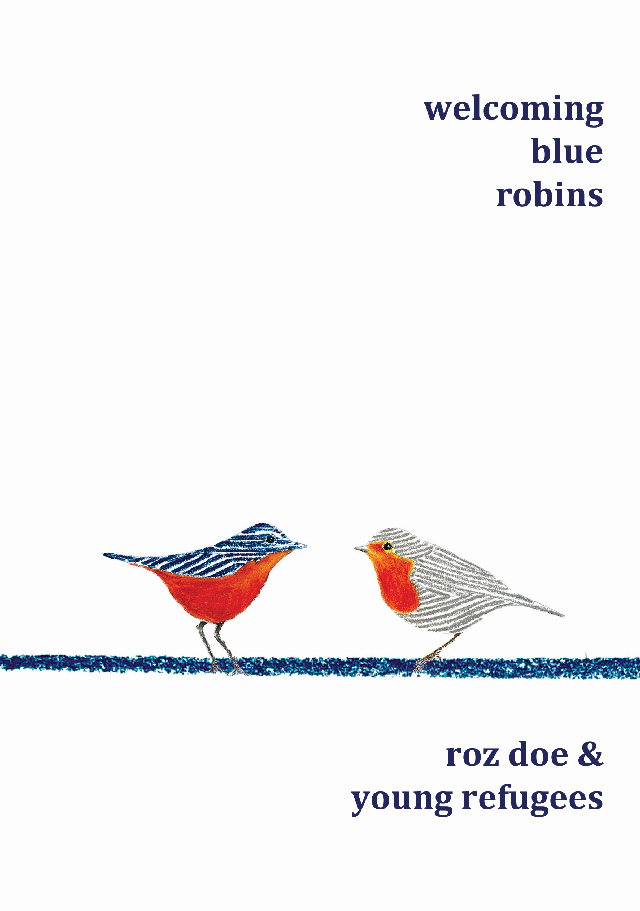

Roz Doe holds an MSc in Forced Migration and has been working with young refugees and asylum seekers for over 20 years. In 2004, she co-founded the charity, Young Roots, which worked with young refugees in Lebanon, Egypt and Nepal and currently provides services for young people living in London. The poems and prose in Welcoming Blue Robins were inspired by young refugees she worked with and the pamphlet also contains poems written by and with young refugees in London.

Welcoming Blue Robins launched in London in June 2024, in Brighton in July and there will be a reading at the Poetry Library in November. You can order a copy from this page for £11.00 plus postage.

***********

Interview with Roz Doe, published in Lapidus, Issue 04, 2024

Writing poems enables me to manage the difficult feelings that accompany being a frontline support worker for young refugees. In 2004, I co-founded a charity, Young Roots, with volunteers I met teaching English to Palestinian children in Lebanon. The charity began providing group activities in London and internationally, aiming to support and empower young refugees. Fast forward to 2015 and Young Roots continued to grow. I had been managing our London programme since 2013 and was expecting my first child in the Autumn. Life felt full of possibility. But everything changed overnight when my youngest brother, who had lived with schizophrenia for 12 years, died having jumped/fallen from a clifftop in Brighton in April. The next year was an intense mix of grief at his loss and joy at my daughter’s arrival.

I returned to Young Roots from maternity leave in January 2017 as a part-time youth caseworker in Croydon, to offer one-to-one support to young refugees, many of whom sought advice at our drop-in youth group. I assisted young people with various issues including mental health problems, accessing education, finding legal advice, and resolving the destitution and homelessness, mostly caused by failed asylum applications. I provided emotional support while we waited for their situations to improve. Having previously delivered group work, offering one-to-one support for refugees and witnessing, up close, the difficulties they experienced, impacted me emotionally in unanticipated ways. I discovered the value of putting my feelings into Morning Pages when I followed Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way in 2014. This book also inspired me to try creative writing and I participated in online poetry courses. On my train journeys to and from work, I wrote about young refugees as a way of processing what I witnessed them experience.

Disentangling personal history from current experience

When starting my casework role, I had not considered how working mainly with young men, many of whom were struggling with their mental health and experiencing suicidal ideation, might affect me. However, I quickly discovered that certain young people reminded me of my brother. I realised in clinical supervision that working with these young people triggered the trauma of losing my brother, constantly reminding me of how I had tried and failed to prevent his death. This also caused me to feel heightened anxiety about those who reminded me of him. It can be difficult to disentangle the impact of my past experiences caring for and losing my brother from the concern I feel when young refugees express suicidal thoughts or present with mental distress. Writing a prose poem, “Something might happen,” Welcoming Blue Robins (pp. 41-44), which explores how my own experiences with my brother influence my response to others with mental health problems, has helped me understand this better.

Processing what I witness: the power of metaphor

Writing poems of witness allows exploration of how this work impacts me emotionally and personally. This process is aided by engaging in clinical supervision or reflective practice. In one session, I expressed to my clinical supervisor how overwhelmed I felt by the extent of the distress and risk experienced by the young people. I felt discomfort related to my lack of capacity to change many of the problems contributing to their situations. The following poem expresses this through metaphor, which assisted in bridging the gap between what I know intellectually and how I feel emotionally.

Tsunami

I land in the chair, open my mouth to speak

a torrent of worry wooshes out:

for the client who received a negative decision last week,

who could be picked up and detained at any moment

because I have not (yet) found him a new solicitor;

for the one who thinks of suicide after making it here

alone, leaving his brother, sick, in Turkey

because I have not (yet) found a counselling service to see him;

and for another, who is still sleeping in the park tonight

because I have not (yet) found a shelter with any space.

The therapist I see for work stops me

reminds me to breathe, tells me

It’s natural to feel you can never do enough

for clients who have lost so much.

I tell him I know he is right.

I can’t fix everything.

But how I can believe and feel

what I know logically inside my head?

He says Maybe a metaphor would help.

I close my eyes and it comes.

It feels like I’m watching

people being swept up and washed away

by a Tsunami, a giant wave

of Home Office rejection letters

lost siblings

no options for anywhere to sleep

after we close our youth club doors

at 8pm on cold, winter nights.

All I can do is throw out flimsy rubber rings

hoping they can cling on long enough to survive:

a phone call to a solicitor to prepare a fresh asylum application

that will take years to process;

a referral to a counselling service with a year-long waiting list;

a few nights sleeping on the floor of a draughty church.

At the end of my hour

the therapist asks if the metaphor helped.

I’m leaving knowing this:

I didn’t create the Tsunami.

I’m doing all I can.

But rubber rings can’t stop the water’s force.

This metaphor enabled me to see that I am not responsible for young refugees’ desperate situations even when I cannot find solutions quickly. Imagining myself giving out rubber rings against a huge tsunami reminds me that the problems young people experience are too vast for any one person or organisation to resolve. As the previous poem mentions, Young Roots runs a drop in youth club in Croydon, where I often first met young people in need of help. This includes young adults who have exhausted their appeal rights and are no longer entitled to accommodation. Although I usually managed to make successful referrals to shelters or hosting schemes, this was never instantaneous. One of the hardest parts of my job was closing our doors at 8pm leaving young people to sleep outside, knowing I could return to my warm home and family.

Boundaries

You slump into the opposite chair.

My shoulders tense when I meet your eye.

You answer my questions, I hold back a sigh

busy myself ticking boxes and stare

down at the form on my clipboard where

I record what happened, the reasons why

you fled, fearing your family could die.

I ask where you live, you tell me ‘nowhere’.

I outline your options in a steady voice

talking of referrals to hostels instead

of flinging open my arms, holding you tight

stepping outside my role with another choice

inviting you home to offer you a bed

not sending you out to the cold, dark night.

This poem expresses my inner conflict about how inhumane this felt, even though I know we work within professional boundaries to safeguard young people. It enables me to share the part of me that wanted to do something else in these situations. Bearing witness to young refugees’ experiences in the UK I have always aspired to share my poems to raise awareness of how our asylum policies increase the suffering that young refugees have already experienced through war, dangerous journeys, loss of family, and needing to start new lives here. Representing the stark realities of how our asylum and social care systems treat the young refugees I work with serves to remind me how important our support continues to be. I want to tell others what is happening in our communities. I am now able to do this more widely with the publication in June 2024 of a book of my poems, Welcoming Blue Robins, which are inspired by my experiences as a Youth Caseworker. It includes ten poems written with and by young people. The poems in this book also celebrate the hope and connection that working with young refugees brings, despite all the challenges they face.

Since starting as a Youth Caseworker, I have discovered that writing poems is part of how I stay well-resourced enough to continue this work. One of my privileges is having choices that the young refugees I work with do not have. This includes being able to step away from this work and stop witnessing the injustices they live with every day. But I do not want to do this. Consequently, poetry writing is an important way of managing the difficult feelings I experience when working in this field and bearing witness to both the suffering and resilience of the young refugees I support.

Contact Information

Camilla Reeve, Senior Editor

© Copyright Palewell Press Ltd 2024

Registered in England. Number 10473109. Registered Office 89 Sheen Lane, London SW14 8AE